EXCLUSIVE: The story of England's 'new Maradona' that never was

Even writing the phrase down now, some 30 years after Sonny arrived into the nation’s conscience, feels inherently wrong and hints at the type of attention he would receive on an almost daily basis.

To understand how this young man with magic in his football boots became so famous so quickly, it’s important to understand the context at the time. Satellite television was still in its infancy. ‘Catch up’ TV and podcasts weren’t even a thing. You got your information from the main four English TV channels - Channel 5 didn’t air until 1996 - radio and magazines.

Your attention span would be exclusively on those media, and Sonny Pike was literally everywhere in the early to mid-1990s. Perhaps it was pre-destined to be that way…

“At six years old, I went to primary school and a friend of mine in the class was into football. Liverpool were the best team with Ian Rush and John Barnes, and we would imitate them,” he said in his exclusive interview with Flashscore.

“He would kick a stone across and I would control the stone and shoot it through the two trees that had like a little metal fence behind. A lot of the time that started going through the metal fence and hit the teachers’ cars. We would do the commentary as if we’ve played, and I turned that into a tennis ball and then eventually football.

“There had never been a school football team before and it was full of year fives and year sixes but I was in year two or three. I was the only kid in my class in the team. I might have been seven or eight by then and all the other kids were 10 and 11.

“Then (a couple of years later) I started to play more grassroots football over Enfield playing fields and I would get a lot of people just come and stop and start watching my game for what felt like no reason. A lot of coaches wanted to talk to me and then eventually, the local papers started to write up little things. I was scoring 100+ goals a season where other kids were scoring maybe 30 goals a season.”

In an age long before mobile phones and social media, where the only influencers of the day were those with a God-given talent, it was inevitable that Sonny would eventually be thrust into the limelight. More so when his father could see the pound signs flash before his eyes.

“I got asked to go on London Tonight (90s TV programme), so they could come and film me, and that was the first time I ever got filmed. I've got the big long hair, I've got golden yellow Quasar boots on, and I scored all four goals.

“Everyone was calling me the boy with the golden boots and then after the game, they started asking me my favourite players, and I said Johan Cruyff, Pele and Maradona,” Sonny continued.

“It got a lot of people's attention and then within I think a few weeks or a few months, my dad just said to me that ‘we've had people come over from Holland they want to come and film you.’ But not just that, there’s a chance they want you to go and play for Ajax and Feyenoord.’”

Nowadays at football clubs across the world there is the academy system or a variation of it. Kids are picked up quite early and the majority are cast aside. There are certainly youngsters who have been released that will have horror stories to tell, and for a variety of reasons, but none of them will ever come close to achieving the level of fame that Sonny Pike did.

“Going out to Holland was a big thing. I actually had a Trans World Sport following me out there, and Blue Peter. When I got there, there were two other Dutch companies like their version of the BBC… so as soon as I turned up there was literally cameras filming on the plane, getting off the plane and everything else, and as soon as I got back (to England), everything sort of exploded massively,” he said.

“To be honest with you, maybe I was just sort of still naive to it but I just wanted to go back to football. When I got back it just went to a so another level but I wasn't interested in being on telly at all. It didn't make any difference to me because at that point I was just a 12-year-old kid.

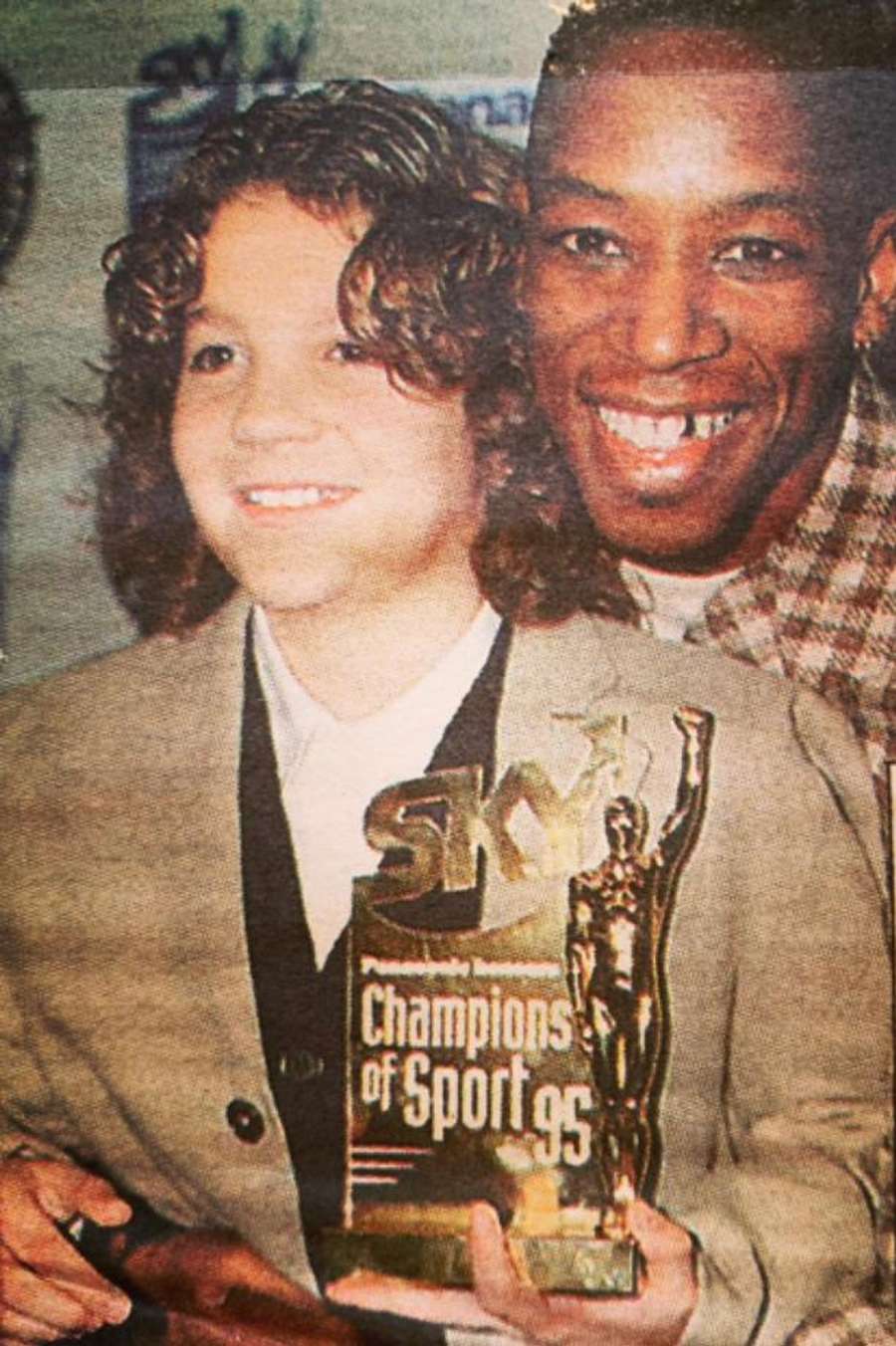

“I was on the pitch for Coca Cola Cup finals doing kick-ups before the games, I was doing McDonald's adverts, I was getting Paul Smith making me suits, I went to his 40th or 50th birthday party and I started to get awards from Sky Sports… at this point in time obviously the Premier League and Sky Sports were just kicking off.

“I was sponsored by Mizuno and was doing things with (Gianfranco) Zola and all these guys but in the early to mid-90s, only one or two players out of a Premier League team would have their own boot deal. People were saying, ‘Who’s this Sonny kid, he's everywhere. He's a little kid, he's got deals, he's going in Hello magazine,’ and it was rubbing some professionals up the wrong way - but I was just a kid getting all this attention.”

As quickly as his fame had arrived, it disappeared, and whilst Sonny’s father was less than pleased, Sonny was grateful that the spotlight had shifted elsewhere. The physical, mental and emotional stress he had been under for years began to take its toll, and Sonny even considered taking his own life after a documentary called ‘Coaching and Poaching’ was aired on Channel Four - and turned out to be nothing like what Sonny had expected.

“It was the pivotal point for me for it, when things literally just went completely the wrong way. Greg Dyke, who ironically ended up being the head of the FA, told me the documentary was just about me doing well but obviously when it came out it was completely different… it was about me being at Leyton Orient and being tapped up by Chelsea,” he added.

“After watching that documentary, I came out of the pub and I stood in the middle of the main road in Edmonton, actually on a roundabout. There's cars just whizzing around me and I just felt that's what my head was getting like. ‘This is too much, enough of this now.’

“Then a month later my dad turns up, I’d not seen him for a few weeks. As soon as he comes up towards me, the first thing I'm gonna say to him is, for the very first time, ‘I don't want to do this no more.’ He told me that he had some more work for me, some more TV stuff and I'm literally about to walk up to and say the complete opposite. He said, ‘If you don't do it, you ain't got a dad.’

“For about 18 months, it goes pretty quiet and I don't see my dad at all. Then I'm trying to get my way back into the game, playing for Crystal Palace and there’s a double-page spread in the News of the World. It's my dad talking about all these clubs and things that they had offered, and how it’s ripped his family apart. That was it, then I just dipped again.

“That's when I found myself driving around on my bike and I felt I could just find myself jumping off a bridge, put it that way. I’d just had enough, my ambitions to be a football player completely gone. I just thought you know what, I need to sort myself out first. And that's what I did.”

Despite everything, and what he thought was once a dream turning into a nightmare, Sonny found the strength and courage within himself to fight back.

He wasn’t going to be defined by a few knockbacks, albeit quite major ones. He simply couldn’t allow his depression to get the better of him, and slowly but surely he began to claw back that bit of himself that had been lost amongst the maelstrom of ‘fame.’

It did take him a long, long time to bury the ghosts of the past and to be able to talk so openly about what had been a horrific experience for him, but as more and more youngsters are bombed out of academies without any clue as to what to do next, Sonny is there to offer a friendly ear and some succinct words of advice. For players and their parents.

“I've ended up doing one-on-one coaching and I've trained kids in small groups as well. I've actually built myself my own little five-a-side pitch and I'm mentoring players. I've talked to loads of young players and I've got a lot of scholars at clubs,” he said.

“I'm talking to their parents and then trying to get the player through that process because obviously I can relate to it a lot - the attention and the pressure they get - I’ve been there.

“I get a lot of other kids come in… a boy was sent down from up north and had a professional contract given to him but he didn't want to sign it. His mum and dad sent him down to me, just to talk to me. I get a lot of that.

“And then obviously, all the technical stuff I used to love doing. That's what I teach kids here, Cruyff turns and all sorts of ball striking…

“To the parent, my first thing is always let their child be in the driver's seat all the time, and always try and set long short-term goals. Don’t too excited straightaway.

“For instance, instead of grabbing all the sponsorship deals and this sort of stuff, getting excited over a few pairs of boots or an advert or whatever else, think long term and concentrate on and promote the love of football more.”

These days, things have come full circle and that’s just fine.

Sonny is also a London black cab driver and he’s even written a book… The Greatest Footballer That Never Was. If it was a novel it would be dismissed as pure fantasy, but every word in the book is true.

At least the ‘greatest footballer that never was’ is still with us to tell the tale, and to sound a warning to any parent keen to open their children up to the pitfalls that could lie ahead.

Sonny Pike’s story is one that will resonate with many and is still as relevant today as it was 30 years ago.